Written By: Sam Ghaleb, Ridgecrest, Calif.

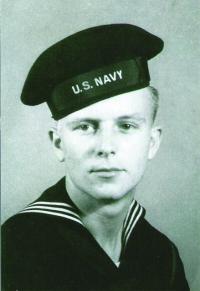

The late Robert E. Wimbrow, from Whaleyville, who served aboard the cruiser USS Brooklyn, which supported the Invasion of Southern France.

General Friedrich Wiese, wearing Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves.

Monument to the landings of Allied troops under General Patch on the beach of St. Tropez, France.

Jacob L. Devers

Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team hiking up a muddy French road in the Chambois Sector, France, in late 1944.

Audie Murphy, most highly decorated soldier in U.S.History, landed with the 3rd Division on Aug. 15, 1944; he won the Distinguished Service Cross for single-handedly killing 8 Germans and capturing 11.

Jean de Lattre de Tassigny

American paratroopers after jumping into southern France near Le Muy in Operation Dragoon, Aug. 15, 1944.

Seventy years ago, on 15 August 1944, Operation Dragoon was launched, nine weeks after the landings in Normandy. The invasion force, which landed on the Mediterranean coast of southern France, included troops from the U.S.,France, and the United Kingdom. This invasion force was not as large as the Normandy D-Day force. However, an armada of more than 860 warships, transports, and various naval crafts had to be assembled in order to land and support the troops on the beaches of the French Riviera.

Originally, the invasion of southern France was named Operation Anvil. It was finally named Operation Dragoon in August 1944. To some of the Allied leaders, the decision to initiate Operation Anvil was a highly controversial one. Launching an invasion in southern France meant that the weight of Allied power in Italy would move west as opposed to going straight into the heart of Europe. To some, this was a signal that a decision had already been taken to leave central Europe – Czechoslovakia, central Germany, and the Balkans – to the advancing Red Army.

The planning for Operation Anvil showed a split between the approaches of American Chiefs-of-Staff and their British counterparts. The same was true between President Franklin Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. For Roosevelt, Operation Anvil was part of what he called the “Grand Strategy,” as was discussed at the 1943 Tehran Conference. Roosevelt believed that a ten division invasion of southern France, combined with the attacks at Normandy, would spilt the German Army in Western Europe in two. Churchill and the British Chiefs-of-Staff expressed their concern that such a concentration of effort and resources would leave Stalin, and his Red Army, with the great prize of central Europe and the Balkans.

However, a combined landing in northern and southern France never occurred. The issue was not political, but rather logistical. General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces, knew that he needed a specific number of landing crafts for D-Day. These landing crafts would require support from a specific number of naval ships that would be transferred from northern France. However, Eisenhower was not prepared to jeopardize D-Day in Normandy by reducing the number of landing craft in northern France. Ultimately, General Eisenhower decided that Normandy was a greater priority and that Anvil would have to wait until the Allies had pushed inland.

Allied Combined Chiefs continued to argue about a landing in southern France even after D-Day. Arguments were advanced for a landing in the Balkans or the Bay of Biscay as alternate choices. Eisenhower originally favored a landing at Bordeaux but recognized that any of the large ports in southern France represented a better choice. Neither he nor General George C. Marshall favored a landing in the Balkans and Marshall publicly questioned why the British would want to land there. Eisenhower needed a deep-water port to land supplies and men. He believed that the ports in liberated northwestern France simply could not cope with the logistical problems of moving and supplying a large number of troops and their equipment. However, the ports of Marseilles and Toulon on the Mediterranean coast of southern France looked promising. Eisenhower had 40 to 50 divisions waiting to be transferred to Europe from the U.S. He knew that the port of Cherbourg in northwestern France could not handle such numbers, but Marseilles and Toulon combined with Cherbourg could.

Churchill continued to argue for the Allies to continue their push up the Italian Peninsula and then into France. This avoided any need for an amphibious landing. If successful, it would also have destroyed the German forces in Italy. Churchill thought that the future of Operation Anvil was truly bleak. He also appealed directly to Roosevelt and reminded him not to sacrifice a successful campaign in Italy for the sake of another.

Roosevelt replied that he would not depart from the “Grand Strategy” discussed at Tehran. He also reminded Churchill that November 1944 was election year in America and that he also had political considerations. A successful Operation Anvil combined with the success in Normandy would put him in a very good political position. The only concession Roosevelt made to Churchill was to rename the campaign Operation Dragoon. Churchill agreed to what Roosevelt wanted, but with no enthusiasm. He informed Roosevelt that the British would do all they could to ensure success but he hoped that Operation Dragoon would not ruin any other “greater project”.

The overall command for Operation Dragoon was given to Lt. General Jacob Devers of the U.S. 6th Army Group. Under Devers, the U.S. 7th Army, commanded by General Alexander Patch, was comprised of the 3rd, 36th, and 45th Infantry Divisions of the VI Corps, and the 1st Allied Airborne Task Force. These forces were led by Lt. General Lucien Truscott Jr. France also contributed their 1st Armored Division under the command General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny. Furthermore, the naval component of the invasion force was under the command of Vice Admiral HK Hewitt of the U.S Navy. It included Naval Task Force 88 composed of six battleships, four aircraft carriers, 20 cruisers, and 98 destroyers.

Opposing the Allies was German Armeegruppe G, commanded by General Johannes Blaskowitz. This armeegruppe guarded the Atlantic coast along the Bay of Biscay, and the French Mediterranean coast. This force included 11 under-strength divisions consisting of aging veterans as well as men of German descent known as “Volksdeutsche”, from Poland and Czechoslovakia. The defense of the invasion area along the French Riviera was assigned to the 19th Army under the command of General Friedrich Wiese. The only battle hardened unit in the 19th Army was the 11th Panzer Division, which fought the Red Army at the greatest tank battle in history, near Kursk, in the Soviet Union, in July 1943. German Armeegruppe G intelligence was aware of an impending Allied invasion. However, the exact area was thought to be around the port of Genoa in Italy. The Germans concluded that the Allied battle plan would consist of airborne and glider operations further up the Rhone River, possibly near Avignon. Their conclusion left them defensively weak along the entire coastline. By September 10, units of Operation Dragoon linked up with Patton’s Third Army, coming from Normandy, while the remainder of Armeegruppe G escaped through the Vosges Mountains, leaving 130,000 of their own surrounded by the Allies. As a result of Operation Dragoon, in four weeks, the Allied pincer movement was established and a southern supply route to the Allies was opened.

In the end, the Operation became known as the “Champagne Campaign.” This name was used by members of the 442nd Japanese-American Regimental Combat Team, which landed in southern France, and spent some time on the Riviera. The Allied losses were moderate for such an operation. The U.S suffered 2,050 killed, captured or missing, and 7,750 wounded. The French suffered more than 10,000 casualties. The Germans, however, suffered more than 7,000 killed, 20,000 wounded, and over 130,000 captured in southern France. Overall, this operation was considered to be a great tactical and strategic success for the Allies.

NEXT WEEK: IS PARIS BURNING?

«Go back to the previous page.