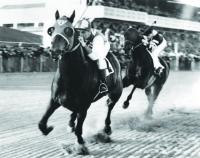

Seabiscuit (front) vs. War Admiral, Pimlico Special, 1938.

Jockey Charlie Kurtsinger Mounted on War Admiral.

Jockey George Woolf on Seabiscuit.

Race card promoting Seabiscuit vs. War Admiral at Pimlico.

War Admiral at Glen Riddle Farm, Berlin MD.

War Admiral winning 1937 Kentucky Derby.

War Admiral winning 1937 Preakness.

Seventy-five years ago, this month, the country was treated to the “Race of the Century,” featuring one of Worcester County’s very own.

No matter what he did, no matter how great he was, no matter how he dominated his sport, he always lived in the shadow of his father. For his father was the greatest that ever lived. Even though he was named the best in his sport, in 1937, and accomplished something his father never did, he could never escape his father’s long shadow. But, the worst was yet to come. And now, the final ignominy - the place where he spent so much time training for his sport, and swimming in Turville Creek - has fallen to the developers. And his stable is now part of a chain restaurant - Ruth’s Chris’ Steak House. The Glen Riddle Farm is now home to, and the restaurant host to, people who had never heard of the great War Admiral, or his immortal father, Man-O’-War.

No matter, War Admiral was, and will always be, a Delmarva Treasure. Of Man-O’-War’s descendants, War Admiral was the most famous - at least until Laura Hillenbrand wrote her #1 bestseller, “Seabiscuit.” War Admiral was foaled, (born), in 1934, in Lexington, Kentucky, at Sam Riddle’s Far Away Farm, but he was soon brought to Berlin, to be trained by George Conway.

Although our story is set in Depression America, it has its beginnings in wartime America. On August 17, 1918, Samuel D. Riddle, a textile manufacturer, from Media, Pennsylvania, paid August Belmont, II, $5000 for a young colt, that became the legendary Man-O’-War. The young colt grew to be a large horse with a chestnut color, which earned him the sobriquet of “Big Red.” “Red” was raised and trained on Mr. Riddle’s “Glen Riddle Farm,” on Route 50, between Ocean City and Berlin. He would go on to be named “Horse of the Year” in 1920, and in 1999, “Horse of the Century.”

As a horseman, Sam Riddle marched to a different drummer. He hated the press, even though, because of Man-O’-War and his offspring, he became one of the most photographed men in sports. “Big Red” didn’t win the “Triple Crown,” because he didn’t race in the Kentucky Derby! Getting from Berlin to Louisville, in 1920, was very difficult, and Sam Riddle felt that the trip was too arduous, and the race was too long, for a young colt. In fact, none of Sam Riddle’s horses raced in the Derby - until 1937 - when, for the first time, he allowed War Admiral to make the trip.

That year War Admiral became the fourth Triple Crown Winner, following Sir Barton, Gallant Fox, and Omaha. He won all three races - the Kentucky Derby, the Preakness and the Belmont Stakes - leading wire-to-wire. That was his style throughout his career - break into the lead out of the gate, and outrun the field to the finish. In her book, “Seabiscuit,” Laura Hillenbrand said that,

“War Admiral had awesome, frightening speed. Once under way, he was too fast for his rivals, too fast even for strategy. He dashed his opponents against their limitations the instant they left the starting gate, leaving them to ebb out like spilling water behind him. In the spring of 1937, he displayed such overwhelming acceleration and stamina that he was never off the lead at any stage of any race. No horse could touch him.”

But he hated the starting gate. He held up the start of the Derby for eight minutes before he was finally in the gate.

The Preakness featured a furious stretch battle with the Number 2 horse in the Derby, Pompoon. War Admiral prevailed by a head. Pompoon was no lightweight. He had sunk the Admiral’s ship the previous year.

On June 5, 1937, the start of the Belmont Stakes was delayed by the Admiral for nine minutes. When the horses were finally started, he blew out of the gate with such force, that his hind shoe gouged an inch-square hunk out of his forehoof, unbeknownst to his jockey, Charlie Kurtsinger. Once he gathered himself, he blew by the field, trailing blood, to finish three lengths in front. When horse and rider reached the Winner’s Circle, and Kurtsinger dismounted, he was horrified to find the winner’s hoof bleeding and his belly covered with blood. Even so, the Admiral broke his father’s Belmont Stakes, and track, record, and equaled the World Record, winning the race in 2:28 and three-fifths.

While the Admiral had been destroying the competition in the “Triple Crown,” and drawing comparisons to his father, his nephew had been making a name for himself on the West Coast. Although Seabiscuit and War Admiral shared the same regal lineage, there were no similarities, except one - speed. War Admiral had the lines. He looked like he was born to run. Although Seabiscuit was 80 pounds heavier than his uncle, he was a half a foot shorter, with legs two inches shorter. Seabiscuit looked like he was born to pull a wagon.

War Admiral spent the summer healing his injured hoof. Seabiscuit spent the summer tearing up the Eastern tracks. Once word was out that War Admiral had resumed training, sportswriters across the land began to clamor for a match race. Tracks began bidding for the match. As Seabiscuit crossed the finish line, at the Continental Handicap, on October 12, 1937, at New York’s Jamaica Racetrack, the fans began to chant, “Bring on War Admiral.” Seabiscuit’s owner, Charles Howard, was all for it. “Old Man” Riddle, however, was another story.

Unable to bring the “Old Man”(he was 75) to the table, Mr. Howard brought Seabiscuit to Maryland, and entered him in three races in which War Admiral was entered. Although, this wouldn’t be a one-on-one match up, it might be the only way Seabiscuit would be able to confront his more famous uncle.

The first race was the Washington Handicap, run on October 30, 1937, at Laurel Racecourse. After several days of rain, the track, on race day, was not to Seabiscuit’s liking, and the decision was made to scratch him from the race. War Admiral won easily, of course, leading, as usual, wire-to-wire.

Next up was the first Pimlico Special, to be run at Pimlico Racecourse, in Baltimore on November 3, 1937. Once again the weather kept the ’Biscuit off the track. Once again the Admiral won. However, Masked General, carrying 28 fewer pounds, did provide some competition.

The third race was the Riggs’ Handicap, to be run two days later, also at Pimlico. This time War Admiral was a no-show. Over the years, Riddle had had problems with the Pimlico people. When head starter, Jim Milton, used tongs on the horse’s lips to get him into the starting gate, for the Pimlico Special, the owner exploded, pulled War Admiral from the Riggs’, and vowed that none of his horses would ever run on that track again!

By a vote of 621 - 602, the sportswriters named War Admiral “Horse of the Year” for 1937, over Seabiscuit. War Admiral, and fellow Triple Crown Winner, Count Fleet, are the only two horses to go undefeated in their three-year-old seasons.

The cries for a meeting, between the ‘Biscuit and the Admiral, became more intense. In the spring of 1938, Westchester Racing Association scheduled a $100,000 winner-take-all match race between the two horses for Memorial Day, May 30, at Belmont Park, in New York. The whole country was abuzz with anticipation, fueled by the sportswriters, and growing with each passing day. Finally, everyone was going to know which of Man -O’-War’s descendants was the fastest.

Millions were being wagered, 95 percent of it on War Admiral. Special trains were chartered from California, Kentucky, Chicago, Philadelphia, and Boston. But on May 24, Seabiscuit’s trainer announced that he had a sore knee and would not race!

The two might still meet. Both were entered in the Massachusetts Handicap, to be run on June 29, 1938, at Suffolk Downs. Once again, weather (fate?) intervened, and Seabiscuit was pulled. War Admiral ran, but during the race he stepped into a hole, stumbled, cut himself, and finished out of the money for the first, and only, time.

The two horses spent the balance of the summer on their respective sides of the continent. Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt, Jr. spent part of his summer trying to arrange a match race between the two at Pimlico, of which he was the majority owner. By this time Howard would agree to just about anything, in order to get the two horses together on the track. Riddle would be the problem. As if he wasn’t cantankerous enough, there was his boycott of Pimlico. But Vanderbilt was persistent and charming. Finally, Riddle consented, on three conditions. They were: (1) that each horse carry 120 pounds; (2) that Belmont’s starter, George Cassidy, handle the task, instead of Pimlico’s starter, Jim Milton; and (3) that the race be started from a gateless walk-up. Vanderbilt agreed, so long as both sides signed a contract and posted a $5,000 forfeit fee. He notified Howard, who quickly signed and sent his money. Vanderbilt hustled over to Riddle’s New York hotel, only to learn that the “Old Man” had checked out. Vanderbilt rushed to Pennsylvania Station, where he caught Riddle as he was about to board the train for Philadelphia. Riddle started backsliding, but Vanderbilt wouldn’t let him board until he signed. As compared to the purse offered by the Belmont, the year before, only $15,000 would be at stake this time. In an effort to reduce the anticipated crowd, the race was scheduled for Tuesday, November 1, 1938.

Seabiscuit’s handlers began plotting their strategy. It was complicated, because Seabiscuit’s regular jockey, Johnny (“Red”) Pollard, was injured and would be unavailable. His friend, George Monroe (“Iceman”) Woolf, would be aboard Seabiscuit on the historic day. Riddle’s condition, regarding the starting procedure, favored his horse. Because of War Admiral’s antipathy for the starting gate, in recent races, he had been starting from the outside, and was, therefore accustomed to starting without a gate. The Seabiscuit team put the month between the execution of the contract and the race to good use, by training their horse to start without the gate.

And then there was the strategy of the race. For that the “Iceman” consulted with “Red” Pollard. The plan that Pollard proposed was unthinkable. He told Woolf that Seabiscuit could beat his opponent off the line, and would beat him to the first turn. To make Pollard’s plan more unbelievable, he told the “Iceman” to let War Admiral catch his horse! Pollard predicted that if Woolf ran the race the way he was told, Seabiscuit would win by four lengths. But to the press, Pollard flat out lied about his team’s strategy. He said that Seabiscuit would concede the lead, and attempt to catch War Admiral in the stretch.

Most thought that if Seabiscuit drew the post position he might have a chance, but War Admiral won the draw. The racing wags said that, “There’s only one horse alive can outrun War Admiral and that’s his pappy.”

Raceday was bright and sunny. Seating capacity at the track was 16,000. By noon, that number was exceeded, with the race not scheduled to start for another four and a half hours. At 3:30 the horses began the long walk from the paddock. By now, 30,000 people were crammed into the clubhouse and grandstand, while 10,000 more crowded into the infield. Another 10,000 anxious fans gathered outside, hoping to catch a glimpse of something. At 4:00, the two rivals stepped onto the track. Sportswriter Grantland Rice related that the throng was, “ . . . keyed to the highest tension I have ever seen in sport.” Although the betters had put their money on War Admiral, most of the average fans were rooting for the underdog, Seabiscuit.

As “Maryland, My Maryland” wafted through the racecourse, the jockeys positioned their mounts for the start. After two false starts, the “Race of the Century” had finally begun! The two great steeds crossed the start line together. For the first thirty yards, they ran neck and neck. Then, slowly, Seabiscuit began to pull away. The radio announcer screamed to 40,000,000 listeners, “Seabiscuit is outrunning him!” As the horses crossed the start line, with 3/16 of a mile to go, Seabiscuit was two lengths ahead. Here, Woolf eased him over to the rail, in front of War Admiral. After a few more strides, the “Iceman” followed Pollard’s advice and eased back.

With five furlongs to immortality, and Seabiscuit a length ahead, Kurtsinger called for more speed from the Admiral. And War Admiral didn’t disappoint. 40,000 throats roared, “Here he comes!” In a few strides, War Admiral was even with Seabiscuit. Coming around the final turn, the two descendants of Man-O’-War ran as one. Slowly, War Admiral eased in front. Then, when he was ahead by a head, the “Iceman” called for more speed from Seabiscuit. As Woolf passed Kurtsinger, he yelled, “So long, Charley!” Although War Admiral stayed with the other horse for a few strides, that was the race. As Pollard had predicted, Seabiscuit won by four lengths.

Even President Roosevelt had delayed a press conference so that he could tune into the broadcast of the great race.

Seabiscuit was named “Horse of the Year” for 1938.

War Admiral was retired to stud the following year. He died in 1959, and is buried beside his father, in Kentucky.

War Admiral won the last battle with Seabiscuit, when, in 1999, he was ranked 11th to Seabiscuit’s 25th, in the “Horse of the Century” voting.

«Go back to the previous page.